Egyptian Collection

Burials of the Rich – Excavations at Harageh, Egypt

Shabti figure

In the digging seasons of 1913-14, the eminent Archaeologist Sir Flinders Petrie was in his element, getting together an excavation team to investigate the sites of Lahun and Harageh under the sponsorship of the British School of Archaeology in Egypt. Both sites are near the entrance to an area called the Fayum, and so Petrie employed Reginald Engelbach to direct the excavations at Harageh so both sites could be excavated at once.

A wide variety of objects were recovered from the cemetery including shabti figures (statuettes) carved in stone, faience and wood, many amulets, beads, jewellery, steles and hundreds of scarabs. Some of these objects made their way into Worcester Museum’s collections.

How did they get from Egypt to Worcester?

At the time, many excavations undertaken by the British School of Archaeology in Egypt were part funded by museums and institutions who all donated money to the digging seasons so that whatever came back would be distributed between those museums. The distribution lists many museums, not just the British isles but also America and the Netherlands. However, interestingly, Worcester is not on that list. So how did we get it?

A photograph of Mr Frost at Harageh

Reginald Engelbach (who left a career as an engineer after falling in love with Egyptology while on a visit to Egypt) put a team together for the season at Harageh, while convalescing from an illness, which included a man called Mr Frost. Unfortunately, not much is known about his role, but we do know that he packed the finds just before they were transported. Mr Frost seems to have acquired some of the Harageh artefacts himself and at some point they were given to Worcester Girls Grammar School. A few years later they were offered to the museum by Miss D Frost, no doubt a relation.

Murders, Dealers and Wonderful Things

13.5cm high 18th Dynasty pot

Reginald Engelbach, lead director of the excavations at Harageh, created reports on the finds and burials discovered at multi-period cemetery site. He not only reported on the site itself, but also described some of the hardships that faced him and his team, painting a vivid picture of their experience.

Discovered before the rich tomb of Tutankhamun, Engelbach mentions the area they investigated, known locally as Gebel et-Tôha or the Desert of Losing One’s Way. He describes arriving at the site at the end of October 1913 and being joined a few weeks later by several of his colleagues from the British School of Archaeology in Egypt. They worked until Flinders Petrie arrived at Lahun Pyramid, not far from Harageh, then several of his colleagues left to join the excavations there. The rest of the British School excavation team were assisted by experienced local workmen from neighbouring villages.

One thing that appears to have irritated Engelbach was the ‘plague of dealers’ which Engelbach refers to as ‘…worse here than at any place I have worked; the nuisance got to such a pitch that I had a trustworthy boy permanently employed to watch every incoming train and keep the dealers in sight until I could put pressure on them to leave the district’.

Collar necklace

The beginning of this colourful report reads almost like an Agatha Christie novel. Engelbach begins by apologising for the delay in writing up his document, stating that the First World War interrupted things somewhat, and goes on to say that one of his party had been viciously murdered by his Kurdish guides on a trip to Mesopotamia, shortly after the Armistice.

The inventory of findings in Harageh’s cemeteries refers to them having been grave-robbed throughout history, but thankfully the robbers did not get everything. It is said that when Howard Carter was asked “Can you see anything?” at the opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb, he replied, “Yes, wonderful things!”. Here is a small selection of Harageh’s wonderful things in Museum Worcestershire’s collection…

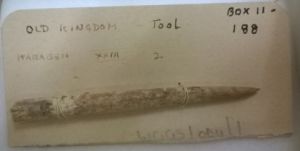

Shaped bone

Little clay pot

Clay pot from Cemetery A

This small nondescript pot is one of the many vessels that was collected from excavations at Harageh. The pot is only 2.5cm tall and came from “Cemetery A”, which comprised of 103 graves and lay on a slight ridge about a mile south of the village of Harageh. The dates of the cemetery comprised of mainly 12th Dynasty Middle Kingdom shaft tombs which would have been around through the eras of the pharaohs Senusret II to Amenemhet III. The Middle Kingdom (2040 – 1782BCE) was generally considered to be Egypt’s age of culture, producing great works of art and literature, made only possible by the stability of the 11th Dynasty.

Little pots like these were found in many funerary contexts and have been interpreted as an offering cup. Some of the funerary rites of the ancient Egyptians would require the living to provide sustenance for the dead in the afterlife. A person’s spirit, called the Ka, required feeding as a living entity, so many pots were interred with substances such as oils, wine, perfumes, sometimes cosmetics. Food was also interred with the burials as well as representations of food. If the deceased was particularly rich or powerful, the grave was made a house for the dead to carry on living in the afterlife.

Ushabti figure

Ushabti’s are among a group of funerary objects called servant figures. First started to be seen in tombs around 2100BC, by 1000BC they were being mass produced – sometimes from moulds. Ushabti’s are thought to act as the servants of the deceased, but they sometimes also represent the tomb owner themselves. In these cases, the ushabti is the home of the Ka, the second body or spirit of the owner which existed to accept food in the afterlife. Many of the hieroglyphs on ushabti figures convey spells to help the dead.

Ushabti’s are among a group of funerary objects called servant figures. First started to be seen in tombs around 2100BC, by 1000BC they were being mass produced – sometimes from moulds. Ushabti’s are thought to act as the servants of the deceased, but they sometimes also represent the tomb owner themselves. In these cases, the ushabti is the home of the Ka, the second body or spirit of the owner which existed to accept food in the afterlife. Many of the hieroglyphs on ushabti figures convey spells to help the dead.