‘Hokusai’s Great Wave: Reflections of Japan’

Celebrating centuries of cultural and artistic exchange between Japan and the west. During 2020, exciting new research was undertaken into the traditional woodcut Japanese prints in the Worcester City collection. This research has revealed more about the artists and stories behind the Japanese characters and scenes depicted. The exhibition explores the impact of traditional Japanese techniques, style and motifs not only on western art but on one of Worcester’s most famous exports – Royal Worcester Porcelain. This exhibition was made possible with a grant from the Weston Loan Programme with Art Fund.

Exhibition

Japan in isolation

Japan’s unique culture and art is in part the result of the country having spent over two hundred years in isolation.

From the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, the only foreigners allowed into the country were a small group of traders confined to an artificial island near Nagasaki, and no Japanese person was allowed to travel abroad. An earlier age of political disruption and civil war was over, leaving the Samurai class largely redundant – retaining their high social status whilst often having very little money. The low-status members of the merchant class, on the other hand, thrived in this peaceful era of isolation, often growing far wealthier than the Samurai. Thanks to the spending power of the merchant class, a vibrant and sophisticated urban culture developed, particularly in the city of Edo (later re-named Tokyo). Theatres, shops, restaurants and public gardens thrived; fashions in clothes and make-up changed, and town-dwellers developed a lively interest in the latest celebrities.

The most exciting and transgressive district of Edo was the Yoshiwara, the pleasure quarter. This was where the brothels could be found, and where the highest-ranking courtesans who paraded in their sumptuous kimonos were famous throughout the city.

The life of the city and the interests of its citizens were recorded in ukiyo-e, woodblock prints, an affordable form of mass-produced art selling for the same price as two bowls of noodles from a street stall. Highly-skilled woodblock cutters and print-makers turned the artists’ designs into vivid images showing popular actors, beautiful women, scenes from history or legend, street-scenes, landscapes, and the latest fads and fashions. Hundreds and thousands of these prints were produced, but they were seen as ephemeral items, and most did not survive.

Japan opens up

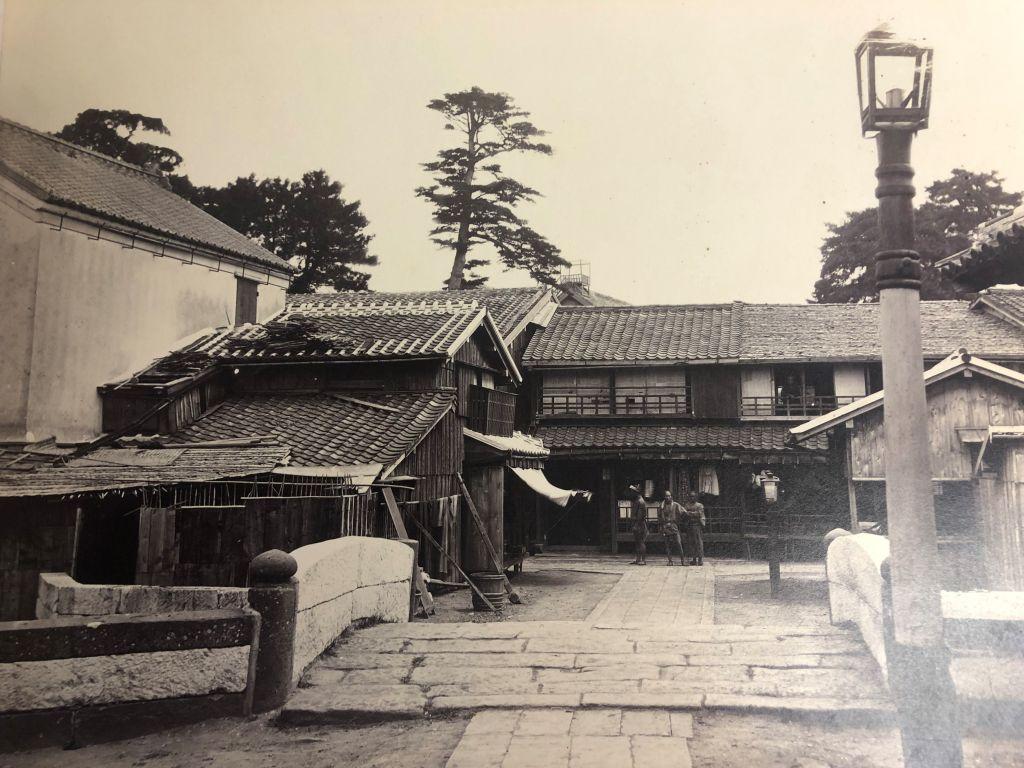

In 1853, American warships commanded by Commodore Perry sailed into Edo (Tokyo) bay, and with threats of violence forced the isolated country to open up to international trade and contact.

Japan quickly adopted Western ideas, technology and dress, significantly disrupting people’s lives and Japanese society. Official missions were organised to observe Western life and choose which aspects of it to adopt. Traditional streets acquired new gas streetlights of Victorian design, and men of the Samurai class cut their hair short, bought business suits, and took on office jobs.

Some groups in society, particularly in the more remote and rural areas, rebelled against this westernisation, wanting to maintain the traditional ways and values. The unrest was quelled, whilst in the cities western ideas and styles came to be seen as modern and progressive.

Many artists and craftspeople had to adjust to the changes because their traditional skills were no longer needed. The ivory-carvers who had made netsuke – toggles used as a part of traditional dress – turned to making decorative carvings, whilst swordsmiths earned a living forging formidable kitchen knives. Others were enthusiastic about the changes, and incorporated them into their work. Visual artists began to experiment with Western art-styles and new materials, whilst ceramicists discovered new techniques and different designs for their pottery and porcelain.

Yet at the same time that the West was changing the face of Japan, Japan itself was having a huge influence on the West.

Artists of the floating world

The mid-nineteenth and twentieth centuries saw the birth of Japonisme, a term pioneered by Philippe Burty in 1872 which refers to the craze for Japanese culture in Europe.

Whilst some objects and artworks appeared in large exhibitions such as the World’s Fair in Paris and Vienna, others were found in less eminent places. James McNeill Whistler discovered prints in a Chinese tearoom in London Bridge. Claude Monet reportedly saw ukiyo-e prints for the first time sold as wrapping paper in Holland.

In Japan, they were so commonplace that nobody thought about the wrapping paper very much. Old discarded prints were cheap paper, and were often used to wrap ceramics when they were packed into the holds of ships. But when western artists saw them they were mind-blown – these images were at once so new but also accessible and relatable.

Whilst separated from early nineteenth century Japanese masters by time and geography, both Impressionists and Post-Impressionists similarly hoped to capture and elevate the real world as Hokusai and other Japanese masters had. Ukiyo-e translates as ‘pictures of the floating world’. It refers to the transitory nature of life, but also to the ‘here and now’, and ‘living in the moment’. The Floating World was one of back streets and ukiyo-e captured the characters and activities synonymous with life lived in the pursuit of pleasure.

Ukiyo-e prints often featured flattened perspectives, and they would sometimes leave the middle-ground of their work empty. The flatness and vibrant colour of Japanese aesthetics must have seemed so liberating, and inspired experimentation with new techniques and compositions.

These were works created by artists in a modern sophisticated culture, and the prints portrayed aspects of life which were recognisable and relatable. One might consider a typical Hiroshige cityscape – it’s a city, a bit different from western cities, but still recognisable as something we would understand, and portrayed in a way that nobody had ever thought of showing a city before. Western artists saw these prints, and afterwards saw their own cities and landscapes through Japanese eyes. Perhaps that’s why Van Gogh copied Hiroshige – trying to understand his way of seeing things and then portraying it himself using his own art.

“If you really, seriously want and need to affiliate me with something, then let it be with the old Japanese. The refinement of their taste has always delighted me and I like the way their aesthetic suggests things; the way it evokes a presence with a shadow, and the entirety of something with a fragment”

Claude Monet

William F Dickson, End of a Weary Day, 1897, oil on canvas. Worcester City Collection. When Worcester City Art Gallery and Museum was built in 1896/7, it was part of the wider Victoria Institute which taught many of those porcelain artists who were incorporating Japanese art and design into their own creations. It is likely that the strong design influences for Royal Worcester at the turn of the century played a part in encouraging early curators to begin to collect fine art in earnest.

Japonisme

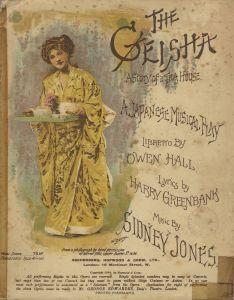

Japonisme had a wide-ranging and far reaching impact on many aspects of western culture. The craze for Japanese style could be seen in interior design, with the creation of imitation gardens, and stylised on theatrical and musical posters and programmes. Japanese decorative arts were just as influential as the graphic arts.

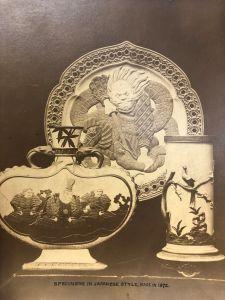

Japanese decorative arts, including ceramics, enamels, metalwork, and lacquerware, were as influential in the West as the graphic arts. During the Meiji era (1868–1912), Japanese pottery was exported around the world. From a long history of making weapons for samurai, Japanese metalworkers had achieved an expressive range of colours by combining and finishing metal alloys. Japanese cloissoné enamel reached its “golden age” from 1890 to 1910, producing items more advanced than ever before. These items were widely visible in nineteenth-century Europe: a succession of world fairs displayed Japanese decorative art to millions, and was also acquired by galleries and fashionable stores.

The Royal Worcester Porcelain Company was founded in 1862, and the company gained recognition with Japanese-inspired designs. In 1872 the Junior Prime Minister of Japan, His Excellency Sionii Tomomi Iwakura, visited Royal Worcester and saw Japanese style wares being made for display in Vienna the following year. Japanese bronzes, ivories and prints, purchased in Europe by RW Binns (Managing Director, Art Director and first company historian), inspired the Worcester craftsmen who did produce replicas, but adapted ideas for the English market.

The House Beautiful

The ukiyo-e in the Worcester City collection mostly date from the early to mid-nineteenth century. Many are by artists from the Utagawa school, which was the most successful ukiyo-e school of the day, training a large number of artists, and characterised by vivid colourful prints of beautiful women, battle scenes, and Kabuki actors. It is not known how they were acquired or who collected them, but the likelihood is that they entered the collection in the 1870s when all things Japanese were fashionable and exciting, with a style and composition unlike anything seen in the West before. There was an intense desire among art-lovers and art students to see some of these images for real.

Oscar Wilde visited Worcester on Tuesday 18 December 1883, giving a lecture at the Worcester Theatre Royal, as part of a nationwide tour. The talk he gave, The House Beautiful, was a revised version of a talk he had given the previous year on a lecture tour of the USA. The text of this lecture was never published and the manuscript has been lost, however a reconstruction of the American version was made by Kevin HF O’Brien and published by the Indiana University Press in ‘Victorian Studies’ vol. 17, no. 4 (June 1974), based on eye-witness accounts and the long, detailed reports carried by the American press. Oscar Wilde’s ideas on home decoration and dress have much in common with those of William Morris but with more of an eclectic and aesthetic approach. Although he doesn’t mention Japanese art much, other than recommendations of Japanese mats, bamboo racks, and ceramics for both decorative and daily use, the underlying message is thoroughly infused with a Japanese sense of style. He emphasises simple elegance and the sensitive use of colours, textures and materials in décor, and uncorsetted dress using beautiful fabrics.

The audience wasn’t large – this wasn’t a mainstream evening’s entertainment – but Berrow’s reports that Oscar told them that, “A more careful arrangement of colour and proportion was necessary to make their houses beautiful,” and that one should avoid glaring white ceilings and, “Never have a large plate glass mirror in the room, nothing could be said for it either morally or artistically.” The underlying message of the lecture, according to Berrow’s was that “The morality of art is merely its beauty, and the immorality of art merely its ugliness”. According to the reminiscences in The Worcester Herald, he advised that children be taught design and drawing at school, and to appreciate “all that was useful and beautiful, and to hate all that was bad and ugly”.

Japanese Woodblock Prints in the Worcester City Collection

Scroll through the image prints above.

Japanese Woodblock prints – ukiyo-e – were popular affordable artworks, produced in large quantities for the citizens of Japan’s bustling and vibrant cities, reflecting the lives, interests and favourite entertainments of the ordinary people. Popular subjects include Kabuki actors, illustrations of well-known tales, city views, and beautiful women. Although they were not considered to be Fine Art when they were made, once they started to appear in the West in the late nineteenth century, these images caused a sensation. They were unlike anything ever seen before, and gave immense inspiration to artists, designers and craftspeople of the period.

Ukiyo-e were cheap, mass-produced artworks, mostly bought by the urban classes for home decoration. They were commercially made in workshops – the artist would create the design, then the publisher’s team of craftsmen would carve the blocks and carry out the printing. It was collaborative work, and artist, woodblock cutter and printer were all seen as artisans rather than artists. The artists’ names and the names of the schools that trained them were something like modern brands. Different schools produced different types and ranges of prints, and the artists often took the name of the school as part of their own name, in the manner of a brand.

The ukiyo-e in the Worcester City collection mostly date from the early to mid nineteenth century. Many are by artists from the Utagawa school, which was the most successful ukiyo-e school of the day, training a large number of artists, and characterised by vivid colourful prints of beautiful women, battle scenes, and Kabuki actors. It is not known how they were acquired or who collected them, but the likelihood is that they entered the collection in the 1870s when all things Japanese were fashionable and exciting, with a style and composition unlike anything seen in the West before. There was an intense desire among art-lovers and art students to see some of these images for real.

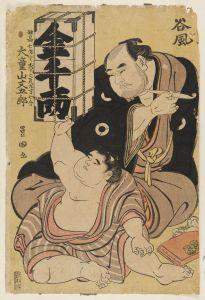

Utagawa Toyokuni I (1769 – 1825) Sumo Wrestlers Tanikaze and Daidozen Bungoro 1794

Toyokuni I was particularly well-known for his portraits of Kabuki actors. He was the son of a doll-maker, and from studying the techniques of other artists, he developed his own style. He studied art under Utagawa Toyoharu, founder of the Utagawa school, the largest school of its day. Students who studied there would be allowed to use the name Utagawa in their professional name if they were deemed good enough. On the death of his master, he took over as the second head of the school and brought it to pre-eminence among the ukiyo-e schools.

Toyokuni I was particularly well-known for his portraits of Kabuki actors. He was the son of a doll-maker, and from studying the techniques of other artists, he developed his own style. He studied art under Utagawa Toyoharu, founder of the Utagawa school, the largest school of its day. Students who studied there would be allowed to use the name Utagawa in their professional name if they were deemed good enough. On the death of his master, he took over as the second head of the school and brought it to pre-eminence among the ukiyo-e schools.

Ukiyo-e artists would typically study under an established master and assume a name that reflected the lineage of their school, often adapting elements of their master’s name into their own, and often adding the name of the school. Their professional names would often change several times during their careers, reflecting increasing maturity, skill and status. Kabuki actors did the same, and still continue the tradition within their clans.

Tanikaze was a well-known Sumo wrestler. Daidozen Bungoro was an eight year old boy wrestler who achieved a brief moment of fame in 1894. Another print, made in the same year by the enigmatic artist Toshusai Sharaku, shows him taking part in the opening ceremony before a Sumo match. Both prints were made to cash-in on an ephemeral fad for the latest celebrity. This print depicts Daidozen Bungoro demonstrating his strength in front of Tanikaze, who is smoking a small-bowled tobacco pipe called a kiseru.

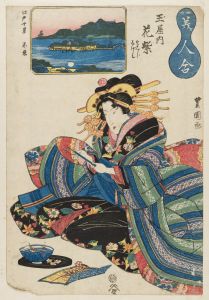

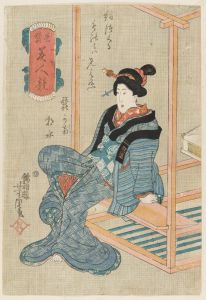

Gototei Kunisada (Utagawa Kunisada/ Toyokuni III) (1786-1865) Tousei Usugeshou (Contemporary Light Make-up) c1825

A print by Kunisada, the most prolific and successful of the ukiyo-e artists, famous for his portraits of Kabuki actors, but overlooked by Western art critics until the 1990s. This was produced to show the latest make-up style, catering for the townswomen who were keen to follow current fashions.

A print by Kunisada, the most prolific and successful of the ukiyo-e artists, famous for his portraits of Kabuki actors, but overlooked by Western art critics until the 1990s. This was produced to show the latest make-up style, catering for the townswomen who were keen to follow current fashions.

This print is signed Gototei Kunisada, though the artist is better known by his later name of Utagawa Kunisada. He was another pupil of Toyokuni, and was the most successful, popular and prolific designer of ukiyo-e in the nineteenth century. During his lifetime, he produced many thousands of different prints, and he made a lot of money from his huge output. He was particularly renowned for his prints of Kabuki actors and plays, which were often vividly-coloured, elaborate and dramatic. This was such a large part of his work that he was nicknamed Yakusha-e no Kunisada – Kunisada the actor painter. Worcester has three Kunisada prints, all of them his less typical bijin-ga images, but still showing his love of sumptuous colours and patterns.

After the death of Toyoshige, Kunisada took over as head of the Utagawa school and assumed the Toyokuni name. He had never accepted Toyoshige’s right to that name and position, and declared himself to be the rightful Toyokuni II, but for the sake of clarity he is now referred to as Toyokuni III in that phase of his life. However Utagawa Kunisada is the name by which he is generally known.

Despite his success and popularity, Kunisada was for a long time dismissed by Western art critics as an inferior and uninteresting artist. Possibly they disapproved of his popularity, financial success or huge output, or found the extravagance and vividness of his prints vulgar. However he was re-evaluated in the 1990s and is now thoroughly acknowledged as one of the great stars of ukiyo-e.

This print shows a courtesan or maybe a tea-house girl, negotiating a ladder-style staircase whilst carrying what appears to be a bowl of tea, and hampered by her elaborate kimono. It is intended as a fashion-plate, intended to display that season’s make-up style, to be bought by townswomen eager to emulate the glamorous yoshiwara look. The date-stamp shows that it was made between 1815 and 1842. Stylistically it probably dates from about 1825

Gototei Kunisada (Utagawa Kunisada/ Toyokuni III) (1786-1865) Tousei Usugeshou (Contemporary Light Make-up) c1825

A print by Kunisada, the most prolific and successful of the ukiyo-e artists, famous for his portraits of Kabuki actors, but overlooked by Western art critics until the 1990s. This was produced to show the latest make-up style, catering for the townswomen who were keen to follow current fashions.

A print by Kunisada, the most prolific and successful of the ukiyo-e artists, famous for his portraits of Kabuki actors, but overlooked by Western art critics until the 1990s. This was produced to show the latest make-up style, catering for the townswomen who were keen to follow current fashions.

This print is signed Gototei Kunisada, though the artist is better known by his later name of Utagawa Kunisada. He was another pupil of Toyokuni, and was the most successful, popular and prolific designer of ukiyo-e in the nineteenth century. During his lifetime, he produced many thousands of different prints, and he made a lot of money from his huge output. He was particularly renowned for his prints of Kabuki actors and plays, which were often vividly-coloured, elaborate and dramatic. This was such a large part of his work that he was nicknamed Yakusha-e no Kunisada – Kunisada the actor painter. Worcester has three Kunisada prints, all of them his less typical bijin-ga images, but still showing his love of sumptuous colours and patterns.

After the death of Toyoshige, Kunisada took over as head of the Utagawa school and assumed the Toyokuni name. He had never accepted Toyoshige’s right to that name and position, and declared himself to be the rightful Toyokuni II, but for the sake of clarity he is now referred to as Toyokuni III in that phase of his life. However Utagawa Kunisada is the name by which he is generally known.

Despite his success and popularity, Kunisada was for a long time dismissed by Western art critics as an inferior and uninteresting artist. Possibly they disapproved of his popularity, financial success or huge output, or found the extravagance and vividness of his prints vulgar. However he was re-evaluated in the 1990s and is now thoroughly acknowledged as one of the great stars of ukiyo-e.

This print shows a courtesan or maybe a tea-house girl, negotiating a ladder-style staircase whilst carrying what appears to be a bowl of tea, and hampered by her elaborate kimono. It is intended as a fashion-plate, intended to display that season’s make-up style, to be bought by townswomen eager to emulate the glamorous yoshiwara look. The date-stamp shows that it was made between 1815 and 1842. Stylistically it probably dates from about 1825

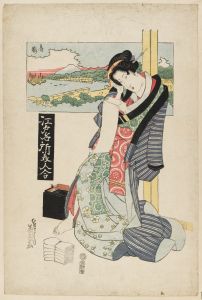

Utagawa Kunisada (Gototei Kunisada/Toyokuni III) (1786-1865) Kinuta Jewel River in the Settsu Province 1835

Another print by the prolific and popular artist Kunisada, personifying a natural wonder as a beautiful woman in a melancholy mood.

Another print by the prolific and popular artist Kunisada, personifying a natural wonder as a beautiful woman in a melancholy mood.

Worcester’s second Kunisada print dates from about ten years later than the first, by which time the artist had taken the name of Utagawa Kunisada. This is a single print from a series of six called Ukiyo mu-tamagawa – Six Jewel Rivers in the Floating World. Japan’s jewel rivers were natural wonders, named because of their beautiful crystal-clear waters. In this series they are used as a basis for idealised images of beautiful women. This woman is elaborately and beautifully dressed in a rich kimono. She is not a courtesan; her obi – the sash around her waist – is tied at the back. Courtesans always tied theirs at the front, for practical purposes and to show their profession.

Kinuta also means a fulling-block, which was used in cloth-making to soften and dry the fabric, and this appears to be what the inserted image behind her shows. The slow, heavy, repetitive sound of cloth being beaten on a fulling-block was traditionally associated with a sense of melancholy and the passing of the seasons, which Kunisada conveys by the woman’s pensive expression and pose.

Utagawa Kunisada (Gototei Kunisada/Toyokuni III) (1785-1865) Bishamonten from the series The Comparison of Lucky Gods to Childish Treasure-Ships Between 1843 and 1846

This is Worcester’s third Kunisada print, displaying his love of rich colours and patterns. One of a series of prints showing beautiful women alongside children dressed as the Seven Lucky Gods of Buddhism. In this case, the child is portraying the warrior-god Bishamonten, who punishes evil-doers and guards the Divine Treasure House.

This is Worcester’s third Kunisada print, displaying his love of rich colours and patterns. One of a series of prints showing beautiful women alongside children dressed as the Seven Lucky Gods of Buddhism. In this case, the child is portraying the warrior-god Bishamonten, who punishes evil-doers and guards the Divine Treasure House.

This is the third print by Kunisada in Worcester’s collection, and is full of his typical rich colours and ornate use of pattern. It comes from a series of seven entitled The Comparison of Lucky Gods to Childish Treasure-Ships, which show beautiful women with children playing at being one of the seven Lucky Gods. This one is called Bishamonten. Bishamonten or Bishamon is a Buddhist deity, portrayed as an armour-clad god of war whose role is to punish evil-doers and to guard the Divine Treasure House. His image is in the circular inset at the top of the print. The Lucky Gods were familiar to all Japanese people at the time, and they often appear in ukiyo-e for a variety of purposes. There are several prints showing Kabuki actors as the gods, there are humorous prints showing the gods in everyday situations, in others they are used to comment on current affairs or the fads and fashions of the day. In this instance, the god is gently parodied by the small boy pretending to be such a fearsome warrior. The focus of the print, of course, is on the woman and her elaborate kimono. Ukiyo-e were often printed in sets or series so that buyers might be encouraged to collect them all.

Utagawa Kunisada II (1823-90) Kameseiro Shoden from the series Pleasing Figures of Today 1867

A print by Kunisada I’s son-in-law and heir, showing a woman musician dressed in the height of fashion, who probably worked as an entertainer in the famous riverside restaurant called Kameseiro, which is still open.

Utagawa Kunisada II was the pupil of Kunisada, married his daughter Osazu, and was adopted by the older artist, going on to inherit his name in 1865. He worked in a similar style to Kunisada I, but was less renowned and far less prolific. By the end of his career, the Kunisada style was falling out of fashion, so he never acquired the renown of his teacher.

This print is from a series of bijin-ga prints called Pleasing Figures of Today. The title of the print appears to relate to the famous riverside restaurant Kameseiro which opened in 1855, and despite the earthquakes, fires and wars that have so often devastated the city, is still open.

The instrument that the woman holds is a samisen, which was often played by geishas and professional musicians to entertain clients. The woman’s soft silk kimono and hairstyle are elaborate; the kimono with its vine-leaf decoration on the lower half was the height of fashion. (At the time the print was made, the all-over decoration of the kimonos in Kunisada I’s prints were out of favour and the current trend was for a plain top half and a highly-decorated lower section.) The likelihood is that she was a musician employed by the restaurant to entertain the wealthy diners at private parties. The outside terrace overlooking the river, with the lights of the far shore shining, would be an ideal setting for an exclusive party on a warm summer’s evening. Her obi is tied at the back, showing that her services went no further than musical entertainment.

Utagawa Yoshikazu (active c 1850-70) Shichibyoe Kagekiyo and Akoya 1857

Yoshikazu is best-known for prints showing the appearance and customs of newly-arrived foreigners in Japan, and for vigorous battle-scenes, but in this print he portrays a legendary warrior and his mistress in contemporary style, as a samurai departing after paying an illicit visit to a courtesan.

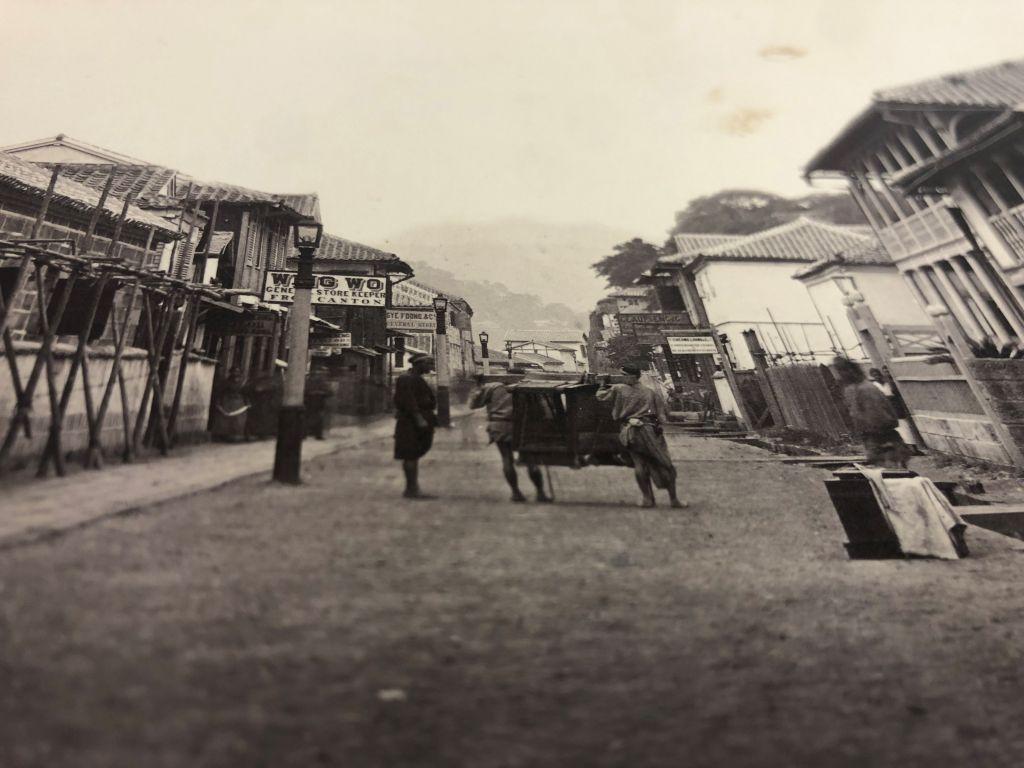

Not much is known about Yoshikazu, except that he was a pupil of the well-known artist Kuniyoshi. He is best known for his numerous yokohama-e, images of the strange-looking Western foreigners who established a business-district and built Western-style houses in the port of Yokohama after Japan opened up to the West in the 1850s. These prints were popular because people all over the country were intrigued by the peculiar appearance, dress and customs of these exotic strangers, who they would be unlikely to see for real. Yoshikazu also made many prints of historical subjects, particularly of armed samurai and medieval battles.

Shichibyoe Kagekiyo was a legendary warrior from the civil war era in the early medieval period, and is usually depicted as a furious samurai in full armour, with a big bristling moustache, taking part in vigorous battle scenes. This print treats the subject very differently. He is taking his leave of his mistress Akoya by a red maple tree, and they are both shown in ‘modern dress’ as a lavishly-dressed 19th century samurai and a high-class courtesan.

Samurai were officially forbidden to visit the yoshiwara, but they did so regularly, typically wearing a big conical hat as a rather unconvincing form of disguise, but still with the swords that made their social class obvious. A samurai who sneaks out to the yoshiwara and falls in love with a courtesan there is a stock character-type in kabuki plays, in which the couples usually come to a tragic end. The incongruity of the great martial hero being portrayed as a modern-day habitué of the yoshiwara would have been obvious to the print’s original owner. It may have been intended as a deliberate comment on the current status of the samurai class, who by this time had largely lost their purpose and wealth, although they retained their social status and sense of superiority.

Utagawa Hiroshige (Ando Hiroshige) (1797-1858) Chikubushima from the series The Summation of the Modern Benten 1823

A rare early print by one of the masters of ukiyo-e, an enigmatic glimpse at life behind the shutters of the yoshiwara, showing a courtesan secretly passing money to a street-musician. The print on the wall shows an island with a shrine to the goddess Benzaiten, and links it to a famous Noh play, also called Chikubushima, suggesting that the courtesan and the musician are not necessarily what they appear to be, but could be avatars of Benzaiten and the Dragon King of the Sea, transposed to the yoshiwara.

Hiroshige was one of the most important ukiyo-e artists of the nineteenth century. He is best known for his landscapes, which were a significant influence on Van Gogh, and his lively view of Edo, showing the sights of the city and people going about their everyday lives. However, up until about 1830 his prints were of more conventional subjects, of actors, warriors and beautiful women. This is a very early print, made when he was still in his 20s.

It is one of a series of bijin-ga entitled The Summation of the Modern Benten. Benten, or Benzaiten, is the only goddess among the Seven Lucky Gods, goddess of luck, eloquence and music.

In this print, a courtesan in a richly-patterned kimono, holding a long kiseru pipe, is in her room in one of the brothels of the yoshiwara, with a print of the island of Chikubushima on the wall. Outside, half-hidden by the heavy wooden shutters, is a street musician, and she is secretly slipping him some money wrapped in a piece of paper.

This enigmatic image appears to relate to a Noh play in which a courtier visits the famous shrine of Benten on Chikubushima in Lake Biwa. He is taken across in a boat by a mysterious old fisherman and a beautiful young woman. When he gets to the island, they tell him about the shrine and he realises that they aren’t human. They then reveal themselves to be the Dragon King of the Sea and the goddess Benten herself. the print links to the story, suggesting that the musician might be seen as the Dragon King in disguise, whilst the courtesan is the form taken by the goddess in the city of Edo.

This is a rare and important print by one of the great stars of Japanese print-making.

Keisei Eisen (1790-1848) Oi of the Ebiya c1830

A portrait of a high-ranking courtesan, parading in front of a flowering peony in an extravagant kimono. One of a series of three prints by a prolific and notorious artist with a particularly close knowledge of the decadent life of the yoshiwara.

A portrait of a high-ranking courtesan, parading in front of a flowering peony in an extravagant kimono. One of a series of three prints by a prolific and notorious artist with a particularly close knowledge of the decadent life of the yoshiwara.

Eisen was a larger-than-life character among the ukiyo-e artists. The son of a calligrapher, he did a number of landscape prints, but the bulk of his output consists of bijin-ga and shunga (erotic prints) reflecting the decadent life of the yoshiwara. His bijin-ga are a mixture of portraits and full-length studies, often of celebrity courtesans like this one. He certainly knew the yoshiwara extremely well; his shunga prints are highly graphic, and his bijin-ga often have a voluptuous sexuality to them. He was a prolific artist, and also a writer. He wrote an account of his life, Notes of a Nameless Old Man in which he describes himself as ‘hard-drinking and dissolute’, and claims that

in the 1830s he owned a brothel called the Wakatakeya, although this burned down in one of the regular fires that were common in the crowded city of wooden buildings.

This sumptuous print shows one of the celebrity courtesans, Oi, from the Ebiya brothel, parading in an exceptionally rich kimono. A kimono like that would have been extraordinarily expensive, and it has several layers of costly under-kimonos to go with it, along with an obi embroidered with the image of a carp. Such kimonos were sometimes given to high-ranking courtesans as gifts from wealthy customers. It would have taken a couple of hours to get fully dressed-up like this, and the outfit would have been very heavy to wear. Her hairstyle too, with all its costly tortoiseshell ornaments, would have taken a long time to do, with hair extensions, pads, and various threads and papers to hold it in place. This would require the services of a skilled hairdresser. Courtesans dressed like this would parade through the yoshiwara on high platform-sandals, with a retinue of attendants, maids, and a servant holding a long-handled parasol, in a colourful, ritualised, and highly theatrical spectacle.

This is one of a set of three prints of named courtesans parading in front of peony flowers. The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam has the full set. This is an important print, and also one of the most decorative in the collection.

Keisai Eisen (1790-1845) Takawana Okido from the series Edo Meisho Bijin Awase 1820s

The second print by Eisen in Worcester’s collection shows the district of the main city gate leading to the famous Tokaido Road to Kyoto, a traditional place for departures and farewells, and a courtesan reading a letter, presumably written by somebody who has left the city.

The second print by Eisen in the Worcester collection is from a series depicting beautiful women alongside famous places in the city of Edo. The image in the background is of the harbour area at Takawana Okido. This is the site of one of the main gates of Edo, originally built for defensive purposes, which marked the boundary of the city and the beginning of the much-travelled Tokaido Road that led to Kyoto. The Tokaido Road was one of the main highways of Japan, and Hiroshige did a famous set of prints showing the sights, towns and landmarks along the road from Edo to Kyoto. As well as the harbour shown here, Takawana Okido had a market and a large number of eating-places. Traditionally, this was where people went to see off friends and family who were leaving the city, a busy bustling place of emotional farewells.

The courtesan in this print is reading a letter, but the letter is enigmatically blank. This may simply be because the artist and print-maker were working to a tight deadline and details were missed, but it may be that she is imagining the letter she wished she had received from someone who has left the city, or maybe it is up to us to imagine what the letter might be saying. A courtesan in the yoshiwara would not be able to travel or leave the city herself, so the freedom that the city gate represents makes a contrast to her own world of confinement.

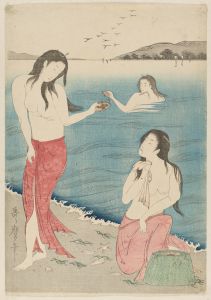

Attributed to Kitagawa Utamaro II (died 1831) Untitled print of Abalone Divers, pre-1820

A print showing three awabe-tori, women abalone-divers, signed Utamaro, but more likely to be by the less renowned Kitagawa Utamaro II than by the great 18th century master of ukiyo-e, Kitagawa Utamaro I.

This is the only print in the collection that does not have a definite artist attribution. It has no publisher’s seal or censor stamp, so it cannot be dated with any certainty. It does, however, have a signature – Utamaro.

Kitagawa Utamaro I (1753-1806) was one of the greatest masters of ukiyo-e. He specialised in bijin-ga and shunga, and produced a number of prints like this one, showing diving-women, some with a near-identical composition to this one. However this print does not seem to have the quality of his work, and its general style and use of colour are not those of an 18th century print.

Utamaro had a pupil, Koikawa Shuncho, who worked with him and possibly contributed to his work at the end of his career when his health was failing. On his master’s death, Koikawa Shuncho married his widow, took over his name, and continued to make Utamaro prints using the same carved signature as his master, so that it is hard at times to be certain whether a print is by Utamaro I or Utamaro II. The likelihood is that this one is by Utamaro II, who continued to use that name until 1820, when he changed it again to Kitagawa Tetsugoro.

The subject of this print is three awabe-tori – women who dive for abalones, which were (and still are) a much-prized delicacy. Diving for shellfish was a tradition in Japanese coastal villages, and it was always done by women, who developed astonishing powers of breath-control. The tradition is continued by a few women, mostly elderly, in some remote parts of Japan today. Of course, the erotic potential of showing bare-breasted women at a time when most Japanese women revealed very little flesh explains the popularity of the subject.

Kinchoro Yoshitora (active 1836-82) Asamizu from the series Yosan Bijinkurube (Comparison of Silk-Cultivating Beauties) Between 1843 and 1846

By a little-known artist with an eventful life, who knew both the traditional life of Edo before Japan opened up to the West, and the modern world of Western-influenced newspapers and journalism. This is one of his early works, an unusual, if idealised, portrait of a silk-weaver.

Kinchoro Yoshitora was one of the lesser-known of 19th Century Japanese ukiyo-e artists, but was very prolific, producing about 60 print series and illustrations to about 100 books. He produced a quantity of yokohama-e (images of the Western foreigners then resident in Yokohama), warrior prints, actor-prints and bijin-ga. He was trained in the Utagawa school as a pupil of Kuniyoshi, and for a time used the name Utagawa Yoshitoro. In 1849 he fell foul of the authorities for satirising the 17th Century Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu in a print which was interpreted as a criticism of government, and he was sentenced to spend 50 days in manacles. Possibly as a result of this scandal, he was expelled from the Utagawa school, and from then on worked under a number of different names. By the 1870s he was doing occasional work as a newspaper journalist, and by the 1880s, most of his work was in book-illustration. His career spans the time from the world of traditional Japan, cut off from the rest of the world, to the beginning of modern Japan, taking the influence of the West to start publishing newspapers and establishing a modern print-media. When this print left Japan on its way to Worcester, he would still have been working, adapting to the rapid changes in the country’s way of life.

This print is one of a series entitled Yosan Bijinkurube, Comparison of Silk-Cultivating beauties. It is thought that there are seven prints in this series, showing the stages of silk production with portraits of the women working on them. This print led to a lot of discussion on the online forum. The writing, in a form of cursive Japanese script deriving from 19th Century handwriting, proved particularly difficult to decipher. Eventually it was shown to a calligraphy-teacher in Japan, whose reading of the silk-weaver’s name is Asamizu, and who transcribed and translated the haiku:-

Shijo sa kuru

Sore to wa mi e nu

Kaiko ka ne

Woven into silk

Never look to be that way

Silkworms!

The print is unusual in being a portrait of a named woman who is not a courtesan, entertainer or celebrity. She is idealised, wearing a kimono and hair-ornaments to which no factory girl could aspire, but still she is presented as a silk-weaver working in an important industry in 19th century Japan, and there is even a suggestion that she might have written the poem herself.

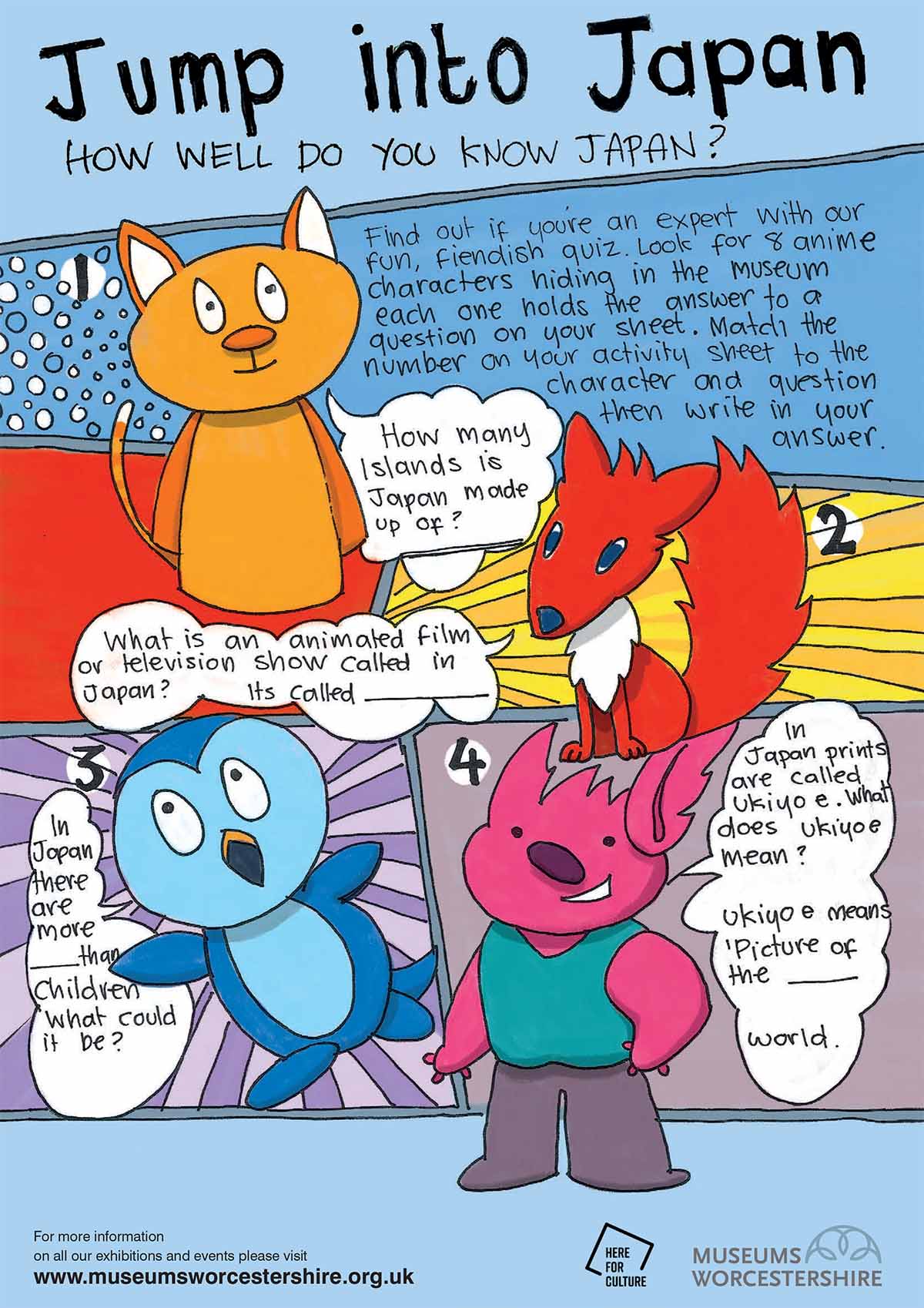

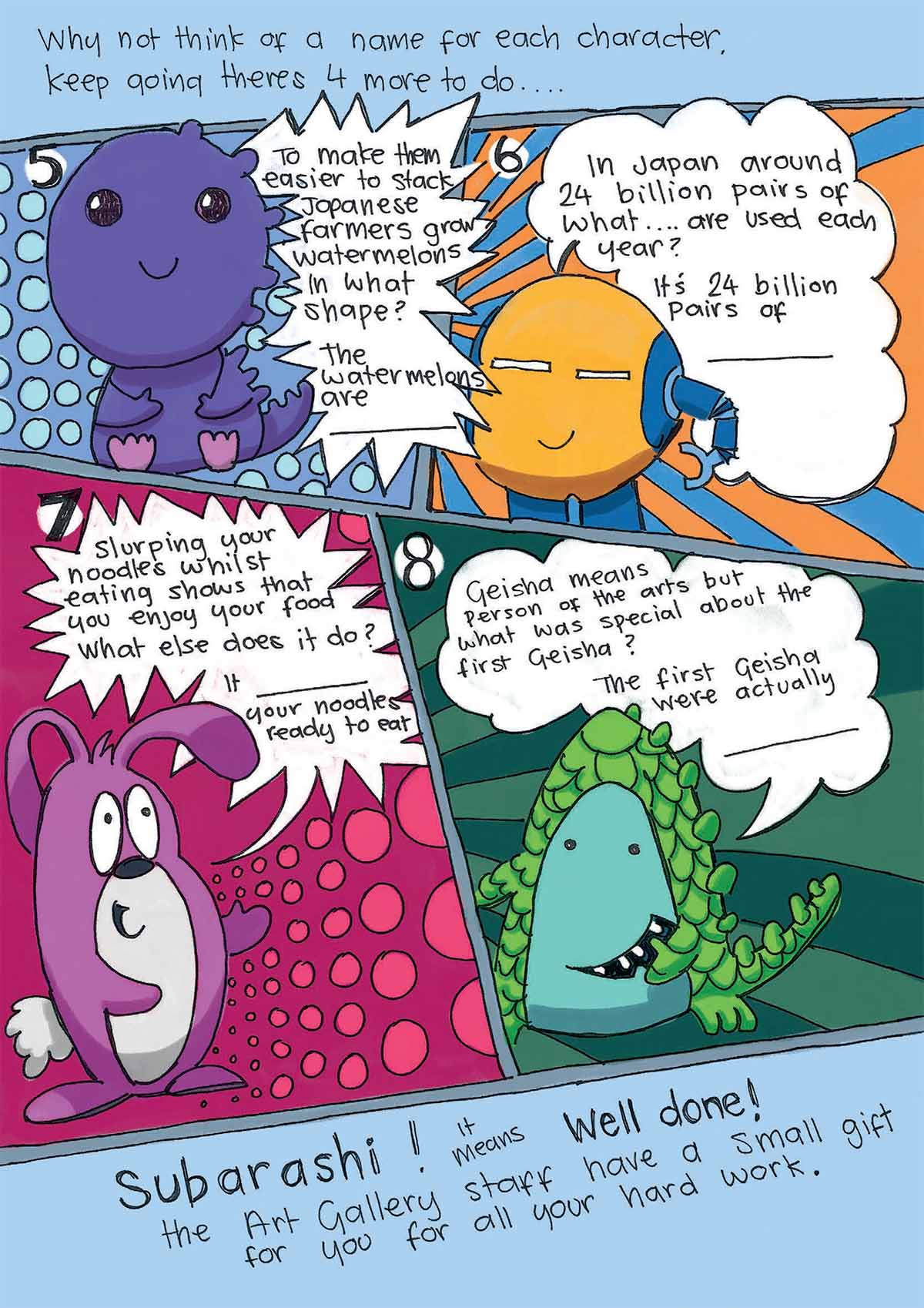

Jump into Japan Trail

How well do you know Japan? Find out if you’re an expert with our fun, fiendish quiz. Look for 8 anime characters hiding in the museum. Each one holds an answer to one of the questions on your sheet. Match the number on your activity sheet with the number on the anime character cards, and write in your answer. £1 per trail, no booking required. A downloadable version of the trail sheet is available here.

Kids will be able to search around the gallery spaces for answer cards, and will receive a prize for completing the trail sheet. Follow the link below for the page of our current Superhero trail – you’ll see that there’s an option to download a digital version of the trail sheet, or purchase one for £1 in the MAG gallery.