Recreation of Bays Meadow Roman Villa in Droitwich.

Roman Worcestershire: On Tracks of Iron & Salt Exhibition

This popular exhibition was displayed in our museums in 2011. While our gallery doors are closed, we bring you an online version so you can enjoy it once more from home!

On this page: Discover the story of Roman Worcestershire, take a 360-degree tour of Bays Meadow Roman Villa which once stood in Droitwich, and enjoy Roman-inspired craft activities for the whole family.

Browse the exhibition

Browse through the text panels, get a close up look at some of the wonderful objects featured in Roman Worcestershire: On Tracks of Iron & Salt. Click the tabs below to move through highlights of the exhibition.

Conquest

Julius Caesar had made the first Roman military expeditions to Britain in 55 and 54BC but a full scale invasion did not occur until AD43

under the Emperor Claudius. Obviously, the county of Worcestershire did not exist then, but it is thought that the area fell largely within the

territory of the Iron-Age Dobunni tribe and it was through this territory that the Roman army passed in the 40s and 50s AD as it pushed west to reach the River Severn on its way to Wales. The native population had to adjust to a new way of life.

Roman conquest relied on building roads and forts. Since the 1950s, a number of possible forts have been suggested for the county for example at Grimley, Blackstone near Bewdley, Perdiswell Hall and Kemerton. Recent investigations suggest that these sites are not forts and have other functions, perhaps as rural enclosures. The best excavated fort in the county is that at Dodderhill, Droitwich which was built, most likely, to secure a major road junction, river crossing and the valuable supply of salt that was produced here.

Features have been discovered such as the ditch of the outer defences with its staggered entrances and near vertical outer edge which made it comparatively easy to cross but much more difficult to retreat. A road and the possible foundations of barracks have also been found. It is thought that it was the XIV legion with their formidable archers that were stationed here at Droitwich.

It has long been assumed that a fort existed somewhere in the centre of Worcester though no structural evidence of it has ever been found. Excavations in the 1960s suggested that the Iron-Age defences were re-dug in this conquest period and artefacts with military associations such as brooches and coins have been found at various places in the city, perhaps lost whilst building the Roman road through Worcester rather than the lost belongings of the garrison of a fort. More recent excavations in St Johns, Worcester have also revealed a possible native trading site which serviced the military on its advance west.

Object in focus… Roman Intaglio

This wonderful Roman intaglio (engraved gemstone), probably depicting the head of Roma, was found at Sidbury in Worcester during archaeological excavations in the 1970s. Roman intaglios were carved from hard stones or gem stones and were usually worn as rings. Prominent individuals displayed them as a mark of status and used them to emboss the wax seals on letters they sent.

Trade & Industry

Worcestershire had three major industries during the centuries of Roman rule; salt production, iron production and pottery manufacture. Together, they suggest a strong local, industrial economy.

Salt had been an important source of international trade before the invasions. Briquetage was a rough ceramic used to make vessels to contain and transport salt and it has been found in large quantities, in and around Droitwich. It is evident that salt was extracted in Droitwich in the Iron-Age and that this continued in the Roman period. By the mid second century AD it appears that its production may have been imperially controlled. Frustratingly, as the Roman period continues, evidence of salt production disappears and it is possible that the centre, or type, of production may have altered. The large wooden barrels found at Droitwich may suggest that brine was used instead of the

extracted salt.

Worcester is best known for its ironworking and is part of a network of industrial ironworking sites that run from Cardiff to Worcester along the River Severn. The iron ore may well have come from the Forest of Dean via river transport or possibly from a closer, now exhausted source. Iron furnaces have been found at Deansway, Broad Street and Pitchcroft but dumped ironworking waste or iron slag as it is called has been found across the city. Evidence of glass making, copper and lead working has also been found in Worcester and a possible jeweller’s hoard from Hindlip has recently been recorded by the Portable Antiquities Scheme. The hoard included well worn coins and quantities of silver and gold.

The Malvern area is well known for its important Roman pottery industry. This produced handmade ‘Malvernian ware,’ similar to pottery produced in the Iron-Age, and a new, wheel-made, Roman type known as ‘Severn Valley Ware.’ This distinctive orange pottery was traded across central western England and has even been found on the northern frontier (along Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine wall). Our knowledge of pottery production in the county is constantly improving; a kiln site was excavated in the 1990s at Newlands Hopfield, Great Malvern. However, we still know very little about the potters themselves.

Object in focus… Jeweller’s Hoard

Part of a Roman hoard found by metal detectorists at Hindlip, Worcestershire. It’s possible the hoard was a jeweller’s hoard and the precious metal in it was intended for reuse. Its discovery was reported through the Portable Antiquities Scheme, the hoard was declared treasure and it was subsequently acquired by Museums Worcestershire.

Town & Country

Droitwich was probably the more important Roman town in the county. The Romans called Droitwich, Salinae, referring to the salt that had been extracted from the local brine water from the Iron-Age and would have been traded with the Romans before the invasion. Salt was a vital part of the Roman economy. Our modern day word for wages, salary, comes from the Latin salarium meaning salt-money. The opulent villa home of the Imperial official who controlled the site has been excavated but the location of the salt worker’s housing has never been found. There must have been a great number.

Worcester was a Roman ‘small town’ which may have been called Vertis, meaning ‘a bend in the river’. The town stood at a junction of the Roman roads which linked Worcester with Droitwich, and the fort at Kingsholme near Gloucester to that at Wroxeter near Shropshire. The river could have been forded at Worcester and it is possible that a bridge may have existed even at this early stage. The town was industrial in character although agricultural buildings and stockyards are also found within the town. Streets lined with timber houses have been found in excavations and evidence of masonry buildings has also been found in the High Street, Britannia Square and more recently at The Butts.

The county is littered with cropmarks left by the Romano-British farmsteads that were typical of rural settlement. Those around the Avon and Carrant valley in the south of the county such as at Beckford, Kemerton and Wyre Piddle differ to those to the north, especially around Holt and Grimley. Different settlement types may reflect different farming regimes and lifestyles. Pastoral farmers would have founded their wealth on cattle whereas arable farmers were more involved in a market economy. Native tradition and the building of roundhouses endured on some rural sites but more Romanised rectangular buildings have also been found. Many of these farmsteads evolved from earlier Iron-Age sites and although the settlements themselves often shifted in location, the field systems that surrounded them were pretty constant.

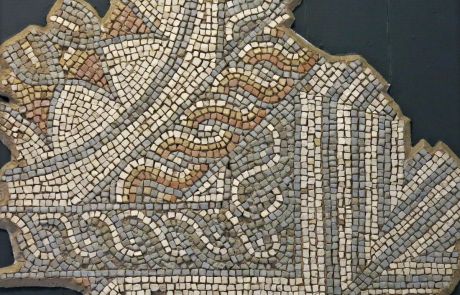

Object in focus… Britannia Square Mosaic

Object in focus… Britannia Square Mosaic

This fine-quality Roman mosaic was found in Britannia Square, Worcester. It is likely to have paved the floor of a high quality townhouse and, although very small, is the largest fragment of mosaic from the city of Worcester.

Each piece of mosaic (made from tile, glass, or stone) is called a tessera.

Bays Meadow Villa

The term ‘villa’ is used to describe Romano-British homes ranging from deluxe palaces to simple farmhouses. The meaning of the term has been much debated by those studying Roman Britain. In Latin it simply means ‘farm’. Over its long history Bays Meadow villa in Droitwich was both a splendid palace and a farm and as with many villas it altered in character and use.

Bays Meadow began to develop around 150 AD when two long corridor villas were built close to each other at right angles. A lime kiln for making the white wash covering a mosaic worker’s hut and a mortar mixing pit have been discovered from this time. One villa was later extended with a covered porch or veranda making it larger and more luxurious than the other. Evidence of field boundaries and corn drying kilns suggests that farming took place on the site during the third century. The status of the villa grew and towards the end of this period it was fortified with a rampart and ditch. The complex was destroyed by fire in the early fourth century but the site remained in use as a high-status dwelling. A new, aisled building had been constructed at the time of the fortifications which became the focus of the villa complex after the fire.

The many rooms of the villa complex revealed evidence of opulent mosaic floors, painted plaster walls, a sophisticated hypocaust system (under-floor heating) and a bath house. Archaeological finds suggest decorated furniture, jewellery and samian ware. Overall the finds suggest that the site was owned by a Roman official, presumably overseeing the nearby salt production, who was able to import a style of living into the area that was usually found in more Romanised towns such as Corinium (Cirencester).

Until recently the only villa that was known in the county was Bays Meadow but recently another villa has been excavated at Childswickham near Broadway and in 2010 another probable villa site was discovered at Bredons Norton which is still being investigated. Both of these villas, in the south of the county, have much in common with the Cotswold tradition of villas.

Object in focus… Bays Meadow Mosaic

Object in focus… Bays Meadow Mosaic

This mosaic is one of two in the collections of Museums Worcestershire found at the site of Bays Meadow Roman Villa, Droitwich. This villa was built in the imperial style, presumably to house an official controlling the natural salt resource.

Family

In the years after the conquest it is likely that most families continued to live in much the same way as they had for generations on rural farmsteads. Evidence of domestic life is often found in the shape of pottery, quern stones for grinding grain, bread ovens and spindle whorls used for spinning wool. As the towns grew it is likely that life for urban families changed. Roman Worcester was known for its ironworking and the noise and heat of the industry can never have been far away. Excavations at Sidbury revealed both workshop type strip buildings and evidence of a female presence such as hairpins and brooches.

Research into ratios in Romano-British cemeteries reveals that an average family had two children. This suggests some element of family planning and classical writers did suggest varying techniques. It is known that infanticide (the killing of infants) was practised in parts of the Empire and infant burials are common on sites in Worcestershire, but pregnancy and childbirth must have been a much riskier process in the Roman period. Cassius Dio recorded that families in Scotland, at least, raised all of their children.

In Roman law women could not be the head of the family. It’s likely that in Roman Britain the laws and morals of the native traditions would have been followed and it may be that tales of women like Boudicca and Cartimandua leading their tribes into battle against the Roman

invaders suggest that at least in the higher levels of native society, women could hold more authority.

Evidence for the lifestyle of women can be difficult to find. Inscriptions and curse tablets can provide evidence. Though none have been found in Worcestershire, an inscription from Templeborough in Yorkshire refers to a woman called Verecunda Rufilia as a tribeswoman of the Dobunni suggesting that she attached significance to her tribal identity. There are artefacts that reveal the presence of women in the county and their tastes in fashion; hairpins, brooches, bracelets and finger rings. Cosmetic pots and scoops have also been found and nail cleaners and tweezers were used by men and women and alike.

Roman tweezers discovered at King Street, Worcester

Religion & Death

Britain already had its native Iron-Age cults and it is thought that the cult of the mother goddess was worshipped within this territory of the Dobunni. The Romans were tolerant of these religions, and merged the local cults with their own classical gods. Later, in the third, fourth and fifth centuries, Christianity became the dominant religion of Roman Britain.

The ritual with which the population disposed of their dead also altered with the change of religious focus although it must be said that the

extent to which local, classical and Christian religion and ritual were practised in the county is still not well understood. The traditional Roman ritual for disposing of the dead was cremation and it dominated in the first and second centuries AD. Cremated remains buried inside pots are known from all over Worcestershire including those found at Mill Street in Worcester. The high status dead were burnt on elaborate pyres and it is possible that burnt bone veneer found at Bays Meadow villa may have adorned such a funerary pyre.

With the growth of Christianity came the dominance of burials. Christian burials were orientated on an east-west alignment but many follow a north-west line in the county suggesting a fusion of rituals. A number of other curious rites are associated with Roman burials in the county. A number of skeletons from the city and county were found with their heads removed and placed in the grave, perhaps to placate the spirit. Individuals were often buried with their boots on to aid their journey to the afterlife and other burial goods are known such as the joint of lamb that was buried with a female in Wyre Piddle or the coloured beads from a grave at Upper Moor.

It was not permitted for adults to be buried within the town and Roman cemeteries are often found outside the boundaries. Worcester wasn’t a formal Roman town and this may not strictly have been the case here. Infant burials however, are often found much closer to domestic sites. A group of nine infants have been excavated recently on the site of the possible Roman villa at Bredons Norton.

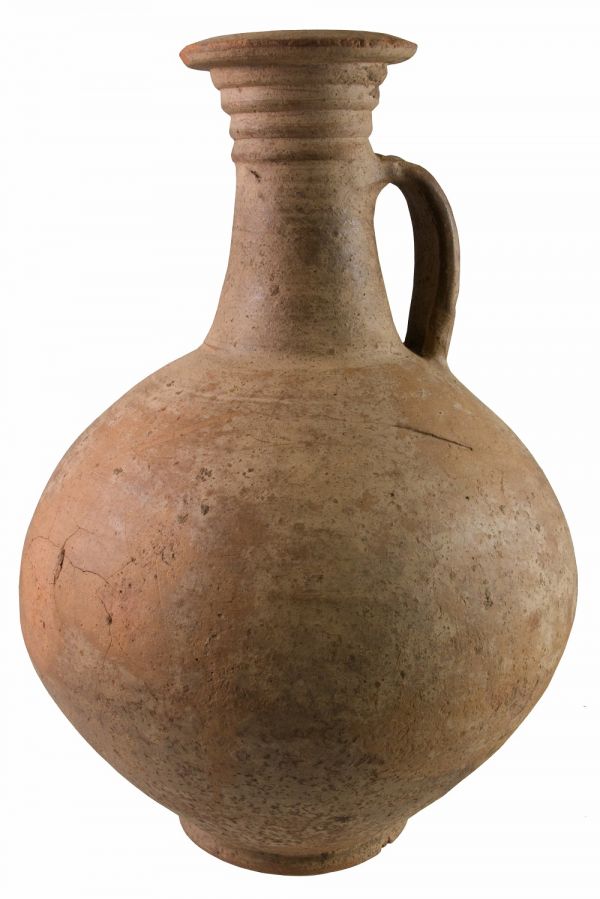

Object in focus… Roman Vessel

Object in focus… Roman Vessel

In 1860 labourers found about twenty Roman vessels whilst digging for sand at Diglis in Worcester at a depth of about 3 to 4 feet. This is one of the best preserved examples. Roman coins and samian ware were also found. Several of the urns contained cremated bone.

An End to Roman Britain

In AD 410, the governor of Roman Britain famously received a letter from the Emperor Honorius informing Britannia that it would have to look to its own defences in the face of barbarian incursions. Rome itself was preoccupied with invaders, having recently seen their city sacked by Alaric and the Visigoths. It was assumed for many years that the legions were withdrawn and with it Roman life in Britain ceased. It is true that with the end of Roman rule went the coinage and the market based economy that had flourished for so long but in many parts of Britain a Romanised lifestyle seems to have continued for some time.

In Worcestershire that may not be the case and the picture that is unfolding is more complex and not well understood. In contrast to a continuation of Romanised culture in some areas, many sites in Worcestershire had declined or been entirely abandoned much earlier than AD 410. At Worcester, the town contracted from the late third century and after AD 400 there are very few finds from the town at all. The archaeological record of the next five centuries is a build up of dark rich earth thought to be the remains of stockyards associated with animal husbandry. There are some features with Roman origins that did persist into the Anglo Saxon period such as the defences, roads and the churches of St Helens and St Albans. This suggests a continuity of some kind of population however difficult it is to find on archaeological sites.

A similar picture is evolving in the countryside with the abandonment of farmsteads by the mid fourth century with no obvious shift in the

location of farms as there had been in earlier centuries. The settlements simply cease. Clearly this is very significant but it is not understood why it occurred and where the population moved to. This end to a Romanised lifestyle applies to industry and objects as much as it does to farmsteads and towns. Production in the pottery kilns of Malvern and the iron furnaces of Worcester simply came to an end.

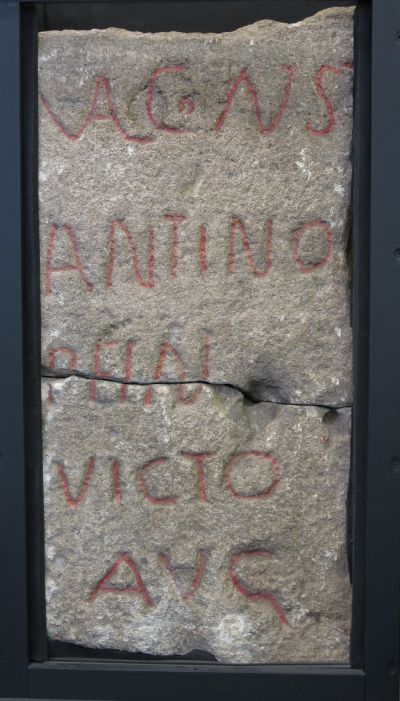

Object in focus… Roman Milestone

Object in focus… Roman Milestone

Roman milestone found at Kempsey in 1818. It was probably inscribed between AD 307 and AD 312. The top and bottom sections are missing. The inscription reads Valerio Constantino Pio Felici Invicto Augusto.

VAL CONST

ANTINO

PF IN

VICTO

AVG

“To the Emperor Valerius Constantinus, Pious, Fortunate, Unconquerable Augustus”.

Acknowledgements

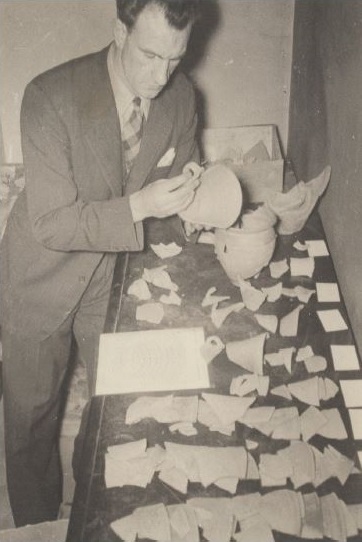

David Shearer with finds from the Market hall site, Worcester

Museums Worcestershire would like to thank a number of people for their help with this exhibition; James Dinn, Sheena Payne-Lunn, Victoria Bryant, Derek Hurst, Hal Dalwood, Robin Jackson and Jane Evans. For many hours spent working on these finds, thanks also go to Lynda Evans, Helen Kirkup, Janet Hogg, Christine Sylvester and Rob Lythe.

Many of the artefacts that are displayed in the exhibition were excavated before archaeology emerged as a profession. From Jabez Allies in the nineteenth century to the pioneers of the Severn Valley Research Group in the 1950s which included Graham Webster, David Shearer (pictured) and Hugh Russell, and more recently, Phillip Barker, Lawrence Barfield and Charles Mundy.

Object in focus… Samian-ware bowl

Object in focus… Samian-ware bowl

This fine Samian ware bowl would have been made and imported from Gaul but was discovered during the building of cellars on the High Street, Worcester.

Objects in focus

Scroll through objects in the exhibition to get a closer look. These items are discussed in more detail in the tabs above.

Explore Bays Meadow Villa

Bays Meadow Villa once stood in Droitwich, suspected to be the grand home of an official who worked in the salt-production industry. From its design and remnants, the image (right) shows how the Villa could have looked during the Roman era. Read the Villa’s history, pieced together from archaeological discoveries, in the Section 4 tab of the exhibition.

360-degree view of the Villa’s interior:

Pighill: Heritage Graphics

Activities

Maximise your family’s learning with our Roman Worcestershire creative activities below. Part of our Museum Make-athon activities released on our social media accounts every Tuesday & Thursday while our museums are closed – designed to get you discovering, exploring and creating together.

Marvellous Mosaics - Museum Make-athon time! ✂️ One of the best Roman mosaics in our collection comes from a home near...

Posted by Worcestershire County Museum on Tuesday, 19 May 2020

Today’s Museum Make-athon ✂️is another Roman one, all about beautiful brooches, badges and buckles to celebrate our...

Posted by The Commandery - Worcester on Thursday, 21 May 2020